| Oye Como Va – Carlos Santana

|

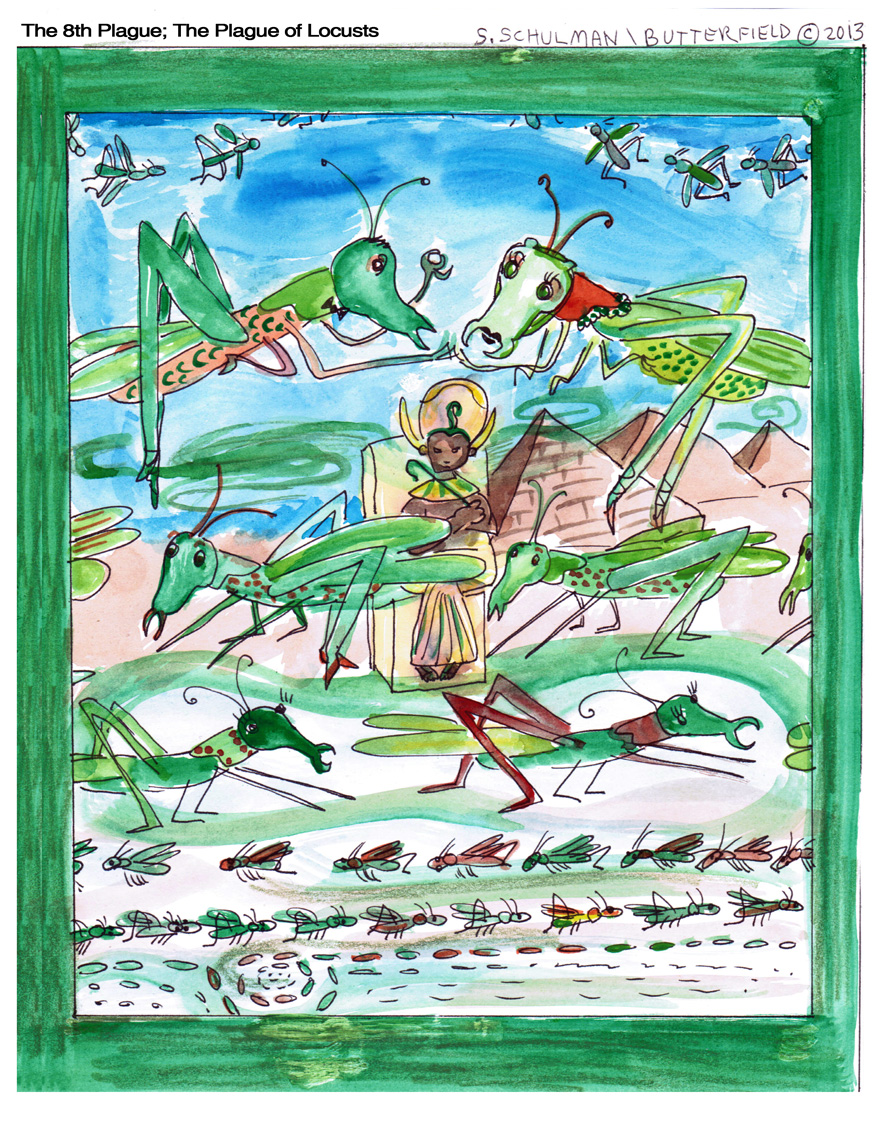

Plague of locusts hits EgyptRoi Kais https://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4351644,00.html Swarm comprised of some 30 million insects descends on Cairo and agricultural farms in Gaza; experts say authorities ignored UN warnings A plague of locusts descended Saturday on agricultural farms in Giza and on Cairo. Egyptian Agricultural Minister Salah Abad Almoman said the swarm is comprised of an estimated 30 million insects and was causing great damage. In Cairo, residents burned tires to create a black fog to keep the locusts from settling in the city. Swarms were also reported to have reached Egypt’s Red Sea city of Zafarana, some 200 kilometers (124 miles) from Cairo, and then the Upper Egyptian city of Qena where locusts appeared in at least three major villages. The Al-Ahram daily reported that since January, swarms of the insects – originating from Sudan – have been spotted along the Red Sea coast in south-eastern Egypt, north-eastern Sudan, Eritrea and Saudi Arabia. In 2004, Egypt witnessed one of the most serious locust infestations in recent history, when farmers in 15 out of the country’s 27 governorates suffered extensive crop damage. The Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture issued a statement saying it had set up task forces to deal with the locust plague. A professor at Cairo University’s Faculty of Agriculture said the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations warned of the locust danger last November, but the Ministry of Agriculture dismissed the warnings as rumors and refused to examine the issue. Professor Nader Nur al-Din claimed that over the past few months he had also warned the ministry of the locust threat. |

-

Today26/09/2025 – ה׳ בתשרי ה׳תשפ״ו

-

Please note that this website uses cookies. Continued browsing of the site constitutes consent to this use.

For more information, see the Privacy Policy.לידיעתך, באתר זה נעשה שימוש בקבצי Cookies. המשך גלישה באתר מהווה הסכמה לשימוש זה.

למידע נוסף ניתן לעיין במדיניות הפרטיותWe recommend you turn off your Ad Blocker.

WE DO NOT ADVERTISE ON THIS SITE.

We do run widgets on the side panel.Jewish Agency Toll Free Phone Numbers

Nefesh B’Nefesh: Live the Dream US & CAN 1-866-4-ALIYAH | UK 020-8150-6690 or 0800-085-2105 | Israel 02-659-5800 https://www.nbn.org.il/ info@nbn.org.il

Nefesh B’Nefesh: Live the Dream

US & CAN 1-866-4-ALIYAH | UK 0800 075 7200 | Israel 02-659-5800 www.nbn.org.il

Grocery Shopping in Israel

English, Hebrew transliterated guide with Meat Chart and Oven Temperatures °F to °C

OCTOBER 7TH POSTS

- ISRAEL AT WAR 5786: Time and Again

- UK and Australia

- France

- ISRAEL AT WAR 5785: Iran: Operation Rising Lion

- ISRAEL AT WAR 5785: Time and Again

- Syria

- Pogroms

- Hezbollah War 5784-5785

- ISRAEL AT WAR 5784: Time and Again

- Hamas on Campus

- 7October

- Am Ysroel Chai עם ישראל חי

- ISRAEL AT WAR 5784: 1 sheep and 70 wolves

- Propaganda vs Reality

- UN, UNRWA and Terror

- You vowed ‘Never Again’

- Prayer for the People of Israel During War

- WAR: Hamas missiles on Jerusalem on Shabbat/Shemini Atzeret 5784

- Never Forget, Never Forgive

- 30 November

- Sanctions

- Erev Tisha B´Av 2014 ערב תשעה באב תשע״ד

- 100th anniversary of the San Remo Conference

- Welcome to the home of the Jewish people

CORONAVIRUS POSTS

- Truth or Consequences Covid-19: The Truth

- They Suffered Myocarditis After COVID-19 Vaccination. Years Later, Some Still Haven’t Recovered

- Watchdog: COVID-19 Vaccines Revealed as ‘Neither Safe, Nor Effective’

- Israeli MOH is hiding a study showing a 2-4 times higher rate of adverse events reports following Pfizer COVID vaccine in kids aged 5-11 vs ages 12-17

- Pfizer-Funded Study Shows Poor Effectiveness for COVID-19 Vaccine in Young Children

- Truth or Consequences Covid-19: More Consequences

- Truth or Consequences Covid-19: The Consequences

- Truth or Consequences Covid-19: More Truth

- Truth or Consequences Covid-19: Save the Children

- Truth or Consequences Covid-19: The Grim Reaper Edition

- Truth or Consequences Covid-19

- Coronavirus COVID-19 Vaccine: Bill Gates “Another Final Solution”

- Coronavirus COVID-19 in the US

- Coronavirus COVID-19 in Israel

- Be Prepared and Stay Healthy

- Wuhan Coronavirus COVID-19 in China

- Bill Gates and the Rockefeller Foundation “Another Final Solution”

GLOBALISM POSTS and Ukraine Posts

- Colour Revolution in Israel

- BRICS

- Buy Locally

- Winter is coming

- Military biological activities of the United States in Ukraine

- News Ukraine Adar 5782

- klopse western

- The Weather report 1 Adar II-5782

- The prophecies are true

- Russia’s Military Operation

- Donbass: Azov Nazi Ukraine Terror

- UKRAINE: DONBASS. YESTERDAY, TODAY, AND TOMORROW

- BURNT ALIVE IN ODESSA. Documentary | 2May2014 Odessa, Ukraine firebombed by Nationalist

- The Dreizin Report – 2022-05-17 – The Fall of the Azov

- Fast Forward to Fascism [Ukraine today]

- Here’s what the Azov Battalion tattoos are hiding

- Interview with a Stormtrooper

- The Azov Battalion: Laboratory of Nazism

“BDS is an anti-Semitic campaign led by supporters of terror with one purpose: the elimination of the Jewish state.” Download the report MSA-report-Behind-the-Mask

Help support a needy Tzadik

Help support Jerusalem Cats

Ministry Of Strategic Affairs Report On “Terrorists In Suits” https://4il.org.il Click to Download the Report.

Click to Enlarge

Uncensored News from Israel and the World

Why Do All These Rabbis Warn Against Getting the Covid-19 Vaccine?

PRAYER TO BE SAVED FROM CORONAVIRUS

Master of Universe, who can do anything!

Cure me and the whole world of the Coronavirus, because redemption is near.

And through this reveal to us the 50th gate of holiness, the secret of the ibbur, and may we begin from this day onward to be strong in keeping interpersonal commandments (i.e. being kind to others).

And by virtue of this may we witness miracles and wonders the likes of which haven’t been since the creation of the world. And may there be sweetening of judgments for the entire world, to all mankind, men women and children.

Please God! Please cure Coronavirus all over the world, as it says about Miriam the prophetess, “Lord, please, cure her, please.”

Please God! Who can do anything! Send a complete healing to the entire world! To all men, women, children, boys and girls, to all humanity wherever they may be, and to all the animals, birds, and creatures. All should be cured from this disease in the blink of an eye, and no trace of the disease should remain.

And all will merit fear of Heaven and fear of God, O Merciful and Compassionate Father.

Please God, please do with us miracles and wonders as you did with our forefathers by the exodus from Egypt. And now, take us and the entire world out from this disease, release us and save us from the Coronavirus that wants to eliminate all mortals.

We now regret all the sins that we did, and we honestly ask for forgiveness. And in the merit of our repentance, this cursed disease, that does not miss men, women, boys, girls, and animals, will be eliminated.

Please God, as quick as the illness came it will go away and disappear immediately, in the blink of an eye, and by this the soul of Messiah Ben David will be revealed.

Please God, grant us the merit to be included in the level of the saints and pure ones, and bless anew all the fruit and vegetation, that all will be healed in the blink of an eye, and we will see Messiah Ben David face to face.

Please God, who acts with greatness beyond comprehension, and does wonders without number. Please now perform also with us miracles and wonders beyond comprehension and let no trace of this cursed disease remain. And may the entire world be cured in the blink of an eye.

Because Hashem did all this in order for us to repent, it is all in order for us to direct our hearts to our Father in Heaven, and by that He will send blessings and success to all of our handiwork.

Important Posts

-

Bill Gates and the Rockefeller Foundation: Vaccine News

-

After Monsey, and New York – Kristallnacht!

- How to help YOUR Relatives Escape from New York

-

A Portrait of Jewish Americans

-

The Jewish People Policy Institute-Raising Jewish Children 2017

- Jonathan Pollard

- We have no other country – אין לנו ארץ אחרת

- You are a Princess

- Modesty for Women – Wig Vs Scarf

-

BDS Know the Facts

- CAMERA: Quantifying the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict’s Importance to Middle East Turmoil

- Warnings to American Jews

- A response to the EU Boycott of Yesha Israel

- Israel is not America

- A School is connected to a Congregation or a Rabbi, Who are they?

- Another reason to use a good Kosher certification hecksher

- Health Risks of Genetically Modified Food or The benefits of keeping Kosher

- What’s in Your Milk? 20+ Painkillers, Antibiotics, and More

- Cholov Yisroel: Does a Neshama Good

- Cell Phones:The Day Einstein Feared Has Arrived

- Death in Advertising – Coke and Cigarettes

- College life in America

- 1 sheep and 70 wolves-Hanukah Geography

- A Heart to Heart talk about Christian missionaries and Jewish Assimilation

- Anatomy of a smear

- Remembering the hard times predating the startup nation

-

Israel: The World’s First Modern Indigenous State

- Rosh Hashanah Foods

- How to assemble an Israeli Succah

-

Hanukkah Posts and Recipes

- 1 January is Sylvester Day יום סילבסטר

- Tu B’Shevat-How and What to check for Bugs

- How to Celebrate Purim

- Purim for Cats: Purim behind the Scenes

- The Day After Purim-How to Prepare for Pesach

- Pesach Tips and Schedule

- Preparing for Pesach

- Sell your Chametz online:

- Pesach Wonder Pot סיר פלא Recipes

- Pesach and Beyond פסח ומעבר

- La Haggada De L’idee Juive

- Counting The Omer ספירת העומר

- Shlissel or Key Challah

- YOM HASHOAH יום שואה

- Yom Hazikaron : יום זיכרון We Remember and Honor our fallen

- Yom HaAtzma’ut- יום העצמאות

-

Shavot Wonder Pot סיר פלא Recipe-Cheesecake

- Tisha B’Av 2013 תשעה באב תשע”ג

- Tisha B’AV Love your fellow Jew

הסערה הבאה שרת התרבות מירי רגב הורתה להכניס ללוגו הרשמי של חגיגות היובל לאיחוד ירושלים את המילה שחרור ירושלים במקום איחוד העיר

נשלח על ידי

איתמר אייכנר

אחרי

Jewish Agency Toll Free Phone Numbers

Nefesh B’Nefesh: Live the Dream

US & CAN 1-866-4-ALIYAH | UK 0800 075 7200 | Israel 02-659-5800 www. nbn.org.il

Alyah : mode d’emploi http://www.jewishagency.org/fr/aliyah/program/7618

Choisissez celle qui vous correspond et inscrivez-vous sur notre site Internet en cliquant ICI ou par téléphone, en appelant le Global Center au 0800 916 647

The Jewish Agency Global Service Center http://www.jewishagency.org/global_centerUS 1-866-835-0430 | UK 0-800-404-8984 | Canada 1-866-421-8912

The Jewish Agency Global Service Center

Point of No Return: Jewish Refugees from Arab Countries

From the 1940s until the 1970s, and heightening with the founding of Israel in 1948, nearly million Jews were expelled from their homes across Arab countries such as Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt, Yemen, Libya, Algeria and Iran.

Jews were frequently subjected to pogroms, systemic violence and religious persecution. Their exiles were largely attributable to Arab regimes increasing their hostility toward Jews because of the very existence of Israel.

Today, while stories abound of many Arab refugees, few are aware or even acknowledge this forgotten exodus of Jewish refugees. Only in Israel has Nov. 30, the day after the UN voted to approve the Jewish-Arab partition plan of Palestine, been marked to commemorate their plight.

Inspirational Breslev teachings in emunah, bitachon and hitbodedut- today!

Breslov Shiurim Podcasts

Subscribe to Podcasts on RSS, iTunes or Poddirectory

Podcasting Help Five Best Podcast ManagersRav Nasan Maimon | Breslov Torah | Free Listening on SoundCloudRabbiisrael on Sound Cloud

The Canary Mission database was created to expose individuals and groups that are anti-Freedom, anti-American and anti-Semitic in order to protect the public and our democratic values.

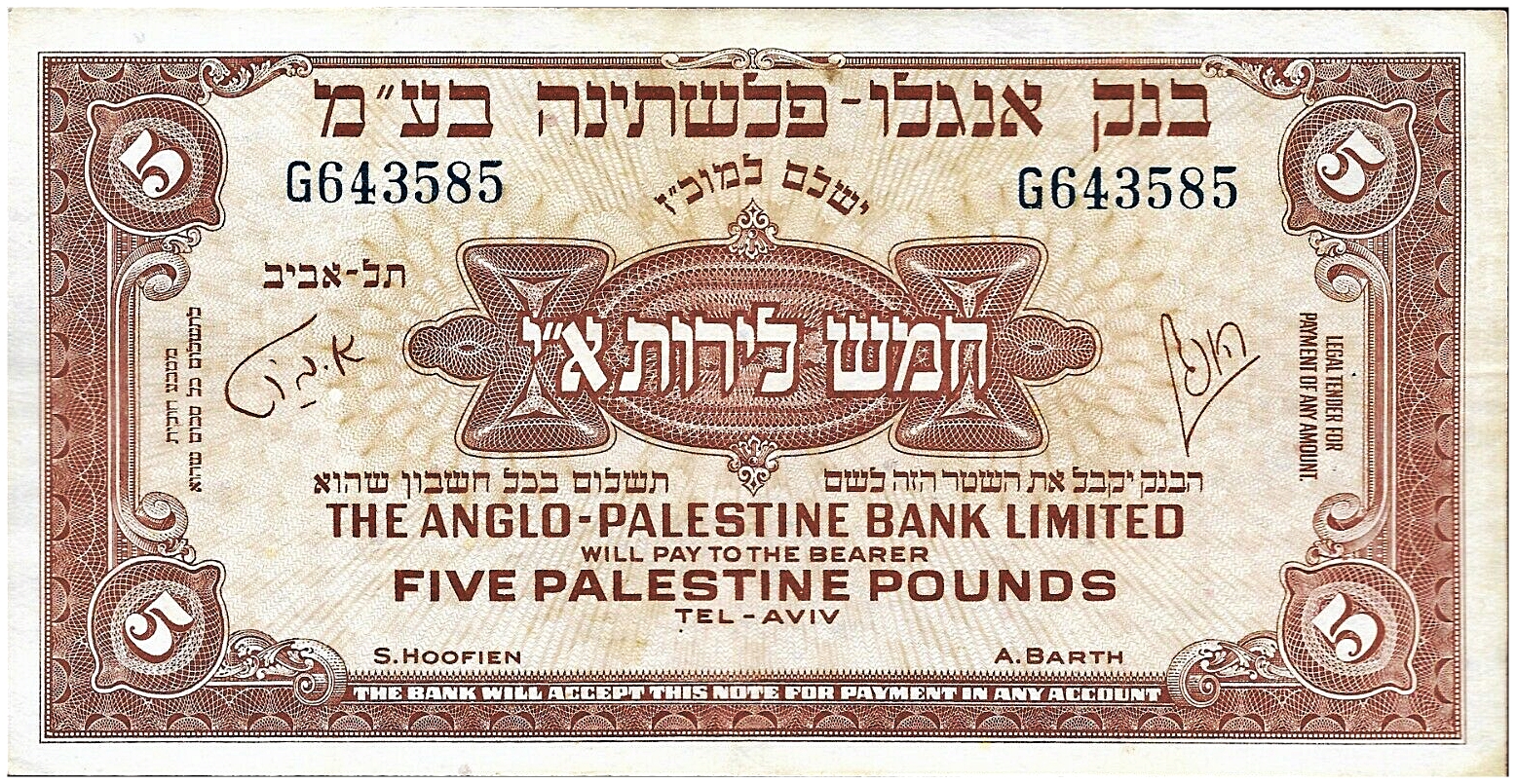

1948 Jewish 5 Palestine Pounds Note

Issuer Israel

Issuing bank Anglo-Palestine Bank Limited

Period State of Israel (1948-date)

Type Standard banknote

Years 1948-1952

Value 5 Palestine Pounds

Currency Palestine Pound (1948-1949)

Composition Paper

Size 105 × 68 mm

Shape Rectangular

Demonetized 23 June 1952

Number N# 207999

References P# 16 September 2025 S M T W T F S 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 -

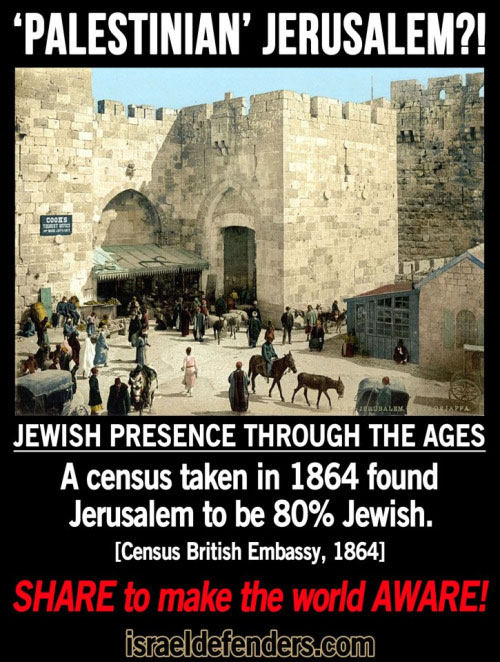

An important piece of evidence: The British Palestine Exploration Fund survey map – 1871-1877 – The PEF people delineated every wadi, every settlement, tree, and home. They crisscrossed the territory, and an examination of the map shows how empty and barren the land was, and how few people lived there.

“The Palestinian people does not exist. The creation of a Palestinian state is only a means for continuing our struggle against the state of Israel for our Arab unity… Only for political and tactical reasons do we speak today about the existence of a Palestinian people… to oppose Zionism.” Zuheir Muhsein, the late Military Department head of the PLO and member of its Executive Council.; March 1977, Dutch daily Trouw

London cab driver’s answer to a request from a Muslim to turn off the radio. (You just got to love the Brits.)

A devout Arab Muslim entered a black cab in London .

He curtly asked the cabbie to turn off the radio because as decreed by his religious teaching, he must not listen to music because in the time of the prophet there was no music, especially Western music which is the music of the infidel.

The cab driver politely switched off the radio, stopped the cab and opened the door.

The Arab Muslim asked him, “What are you doing?”

The cabbie answered, “In the time of the prophet there were no taxis, so get out and wait for a camel.”I wonder how many years (hundreds for sure) Jewish people have lived in Quebec. I don’t believe that they have ever demanded that pork be removed from the school’s menu where their children attend…

Excellent reply by the Mayor of Dorval, Quebec, to the demands of the Muslim population in his community.

Put some pork on your fork.

Too bad the USA doesn’t have the common sense to publish this nationwide, even if they have a muslim in the white house. Should also be posted on signs all along U.S. borders.Let’s hear it for a Quebec mayor.

MAYOR REFUSES TO REMOVE PORK FROM SCHOOL CANTEEN MENU. EXPLAINS WHY

Muslim parents demanded the abolition of pork in all the school canteens of a Montreal suburb. The mayor of the Montreal suburb of Dorval, has refused, and the town clerk sent a note to all parents to explain why..

“Muslims must understand that they have to adapt to Canada and Quebec, its customs, its traditions, its way of life, because that’s where they chose to immigrate.

“They must understand that they have to integrate and learn to live in Quebec .

“They must understand that it is for them to change their lifestyle, not the Canadians who so generously welcomed them.

“They must understand that Canadians are neither racist nor xenophobic, they accepted many immigrants before Muslims (whereas the reverse is not true, in that Muslim states do not accept non-Muslim immigrants).

“That no more than other nations, Canadians are not willing to give up their identity, their culture.

“And if Canada is a land of welcome, it’s not the Mayor of Dorval who welcomes foreigners, but the Canadian-Quebecois people as a whole.

“Finally, they must understand that in Canada ( Quebec ) with its Judeo-Christian roots, Christmas trees, churches and religious festivals, religion must remain in the private domain. The municipality of Dorval was right to refuse any concessions to Islam and Sharia.

“For Muslims who disagree with secularism and do not feel comfortable in Canada, there are 57 beautiful Muslim countries in the world, most of them under-populated and ready to receive them with open halal arms in accordance with Shariah.

“If you left your country for Canada, and not for other Muslim countries, it is because you have considered that life is better in Canada than elsewhere.

“Ask yourself the question, just once, “Why is it better here in Canada than where you come from?”

“A canteen with pork is part of the answer.”

If you feel the same forward it on.

This reminds me of a Morty Dolinsky story from the time he was head of the Government Press Office:

When the late Morty Dolinsky was in charge of the Government Press Office in the 1980s, he once famously replied to a reporter, who asked for information about the West Bank, that he knew no West Bank as he banked at Leumi. -

Archives

-

Pages

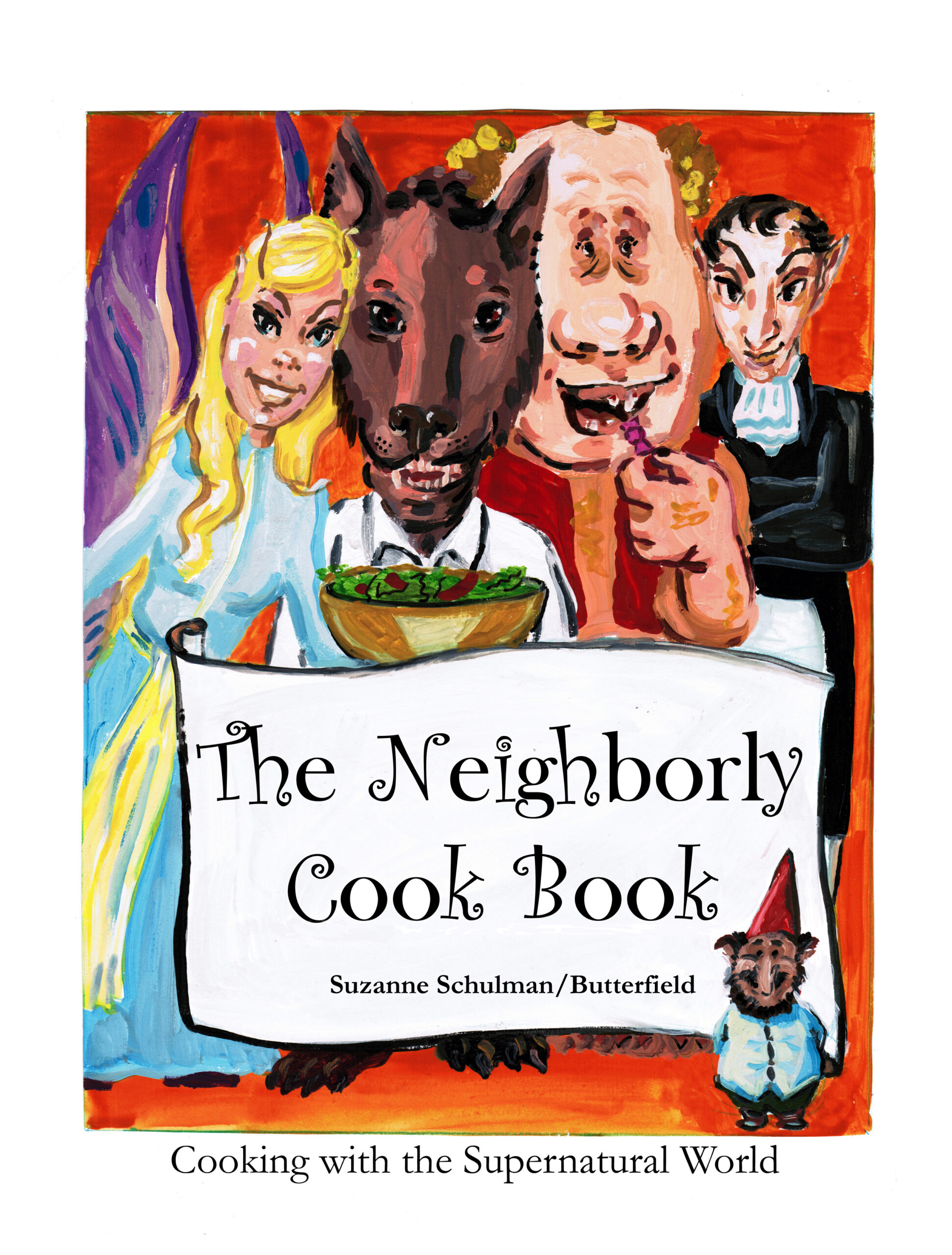

- About the Artist, Cookbook & Novels

- Aliyah Tips

- Aliyah, Health & News

- 100 Years After Balfour Declaration, The Arabs Have Failed Where Israel Has Excelled

- Aliyah Outer Limits Archive

- Aliyah Outer Limits News

- CAMERA – BACKGROUNDER: The Intrinsic Antisemitism of BDS

- CAMERA: Quantifying the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict’s Importance to Middle East Turmoil

- Jonathan Pollard

- Mr. Happy Good News

- Mr. Happy’s Aliyah Outer Limits

- Mr. Happy’s Banned Health News

- Mr. Happy’s GMO – Genetically Modified Food News

- Mr. Happy’s Health News

- Mr. Happy’s Nuclear News

- Mr. Happy’s Past Weekly Column

- Mr. Happy’s Weekly Column

- Mr. Happy’s Wellness Page

- Mr. Happy’s World News

- Not in the News

- Other News

- Astrology, Gematria & Recipes

- Breslov

- Cat Quintet and Cat Videos

- Cat Quintet: Aurora – The Andrews Sisters

- Cat Quintet: Beach Boys

- Cat Quintet: Bei Mir Bist Du Schon – The Andrews Sisters

- Cat Quintet: Besame Mucho – Xavier Cugat and His Orchestra

- Cat Quintet: Best Meditation Music – Oliver Shanti

- Cat Quintet: Let’s Call The Whole Thing Off

- Cat Quintet: Steppenwolf – Magic Carpet ride

- Cutest Cat Moments Videos

- Debbie’s Worm

- For a-sweet boy, I will always remember

- Sons of the Pioneers – What this Country Needs

- Sons Of The Pioneers: Dixie

- You Are My Sunshine

-

Spam Blocked